Is Type 1 Diabetes a Pediatric Disease or an Endocrine Specialty? The Case for Primary Care Screening

The medical community faces a critical question about Type 1 Diabetes (T1D): Should we view autoimmune insulitis leading to pancreatic failure as primarily a pediatric illness?

The medical community faces a critical question about Type 1 Diabetes (T1D): Should we view autoimmune insulitis leading to pancreatic failure as primarily a pediatric illness requiring early detection in primary care, or continue treating it as an endocrine specialty condition diagnosed only after clinical presentation? The answer has profound implications for how we protect children from preventable complications and death.

The Silent Disease That Begins in Infancy

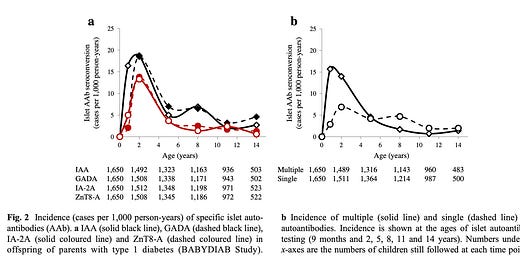

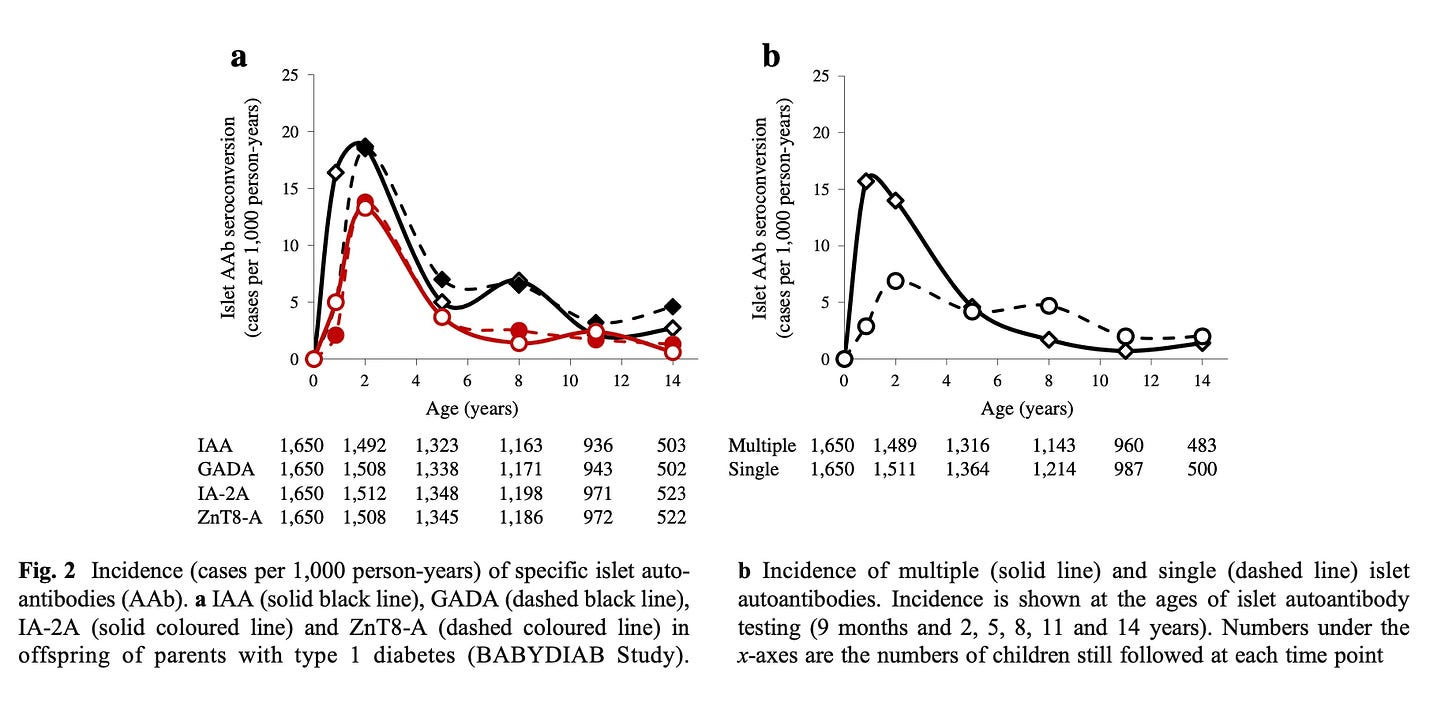

Type 1 Diabetes doesn't announce itself with fanfare. Like hypertension or anemia, it progresses silently through predictable stages long before clinical symptoms appear. What makes T1D particularly insidious is how early this process begins—autoantibodies can be detected and peak between 9 and 18 months of age, years before a child shows any outward signs of illness.1

This timeline reveals a fundamental truth: Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is not a sudden-onset disease that strikes unexpectedly. It's a chronic autoimmune process that follows a measurable trajectory, making it inherently screenable and, crucially, preventable in terms of its most dangerous complications.2

The Epidemiological Reality

The numbers tell a compelling story about why T1D belongs in pediatric primary care:

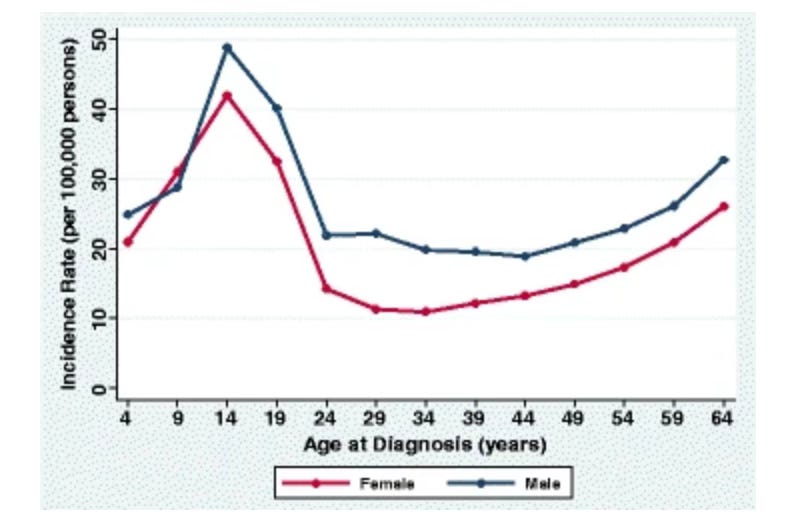

Peak incidence occurs between ages 10-14, squarely in the pediatric population3

90% of at-risk children have no family history of T1D or autoimmunity, making family history an inadequate screening tool

A simple capillary blood draw in any clinic can detect the disease before symptoms appear

Universal screening potential exists, unlike many conditions that require complex risk stratification

This epidemiological profile describes a disease that behaves exactly like other conditions we routinely screen for in pediatric primary care—common enough to warrant population-level attention, detectable through simple testing, and catastrophic if missed.

The Deadly Cost of Late Diagnosis

The consequences of our current approach—waiting for clinical presentation—are measured in preventable suffering and death. Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) at T1D presentation carries a mortality rate of 3 per 1000 cases. To put this in perspective, this exceeds the mortality rate of measles (1 per 1000), a disease for which we maintain robust prevention programs.

When children present in DKA:

100% require Pediatric Intensive Care admission

Many need prolonged hospitalization

Families experience traumatic emergency presentations instead of planned, supported transitions to insulin therapy

Children suffer preventable acute complications including dangerous weight loss and metabolic derangement

The Promise of Early Detection

Early identification through primary care screening transforms the T1D journey entirely. When diagnosed in the presymptomatic stage, families gain invaluable advantages:

Anticipatory Guidance: Parents can learn about T1D progression, understand what to watch for, and prepare emotionally and practically for the transition to insulin therapy.

Prevention of DKA: Armed with knowledge and monitoring tools, families can recognize early symptoms and seek treatment before reaching the dangerous state of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Preserved Agency: Instead of experiencing T1D as a medical emergency that happens to them, families become active participants in managing a known condition.

Access to Emerging Therapies: Early detection opens doors to disease-modifying treatments that delay the need for insulin therapy.

The Endocrinologist's Essential but Different Role

None of this diminishes the critical expertise that pediatric endocrinologists bring to T1D care. However, their role is fundamentally different from that of primary care clinicians in the T1D trajectory.

Endocrinologists excel at:

Managing complex insulin regimens

Providing disease-modifying therapies

Handling advanced complications

Leading care teams once insulin therapy begins

But endocrinologists, by the nature of their specialty practice, encounter patients at the end stage of the disease process. They see children after pancreatic beta-cell function has significantly declined, often after DKA presentation, when prevention opportunities have passed.

A Model for Integration, Not Competition

The question isn't whether pediatricians or endocrinologists should "own" T1D—it's about optimizing care delivery across the disease spectrum. The ideal model recognizes that:

Primary Care Role: Screen, detect early, provide anticipatory guidance, prevent DKA, and coordinate care during the presymptomatic phase.

Endocrinology Role: Lead treatment teams once insulin therapy begins, manage complex cases, provide disease-modifying treatments, and handle specialty care needs.

This collaborative approach mirrors successful models in other pediatric conditions where primary care providers screen and detect while specialists manage treatment.

The Path Forward

Treating T1D as a pediatric primary care screening priority doesn't diminish its complexity or the expertise required for management. Instead, it acknowledges the disease's natural history and leverages our healthcare system's strengths to protect children.

We have the tools to detect T1D early. We understand its progression. We know the devastating consequences of late diagnosis. What we need now is the recognition that autoimmune insulitis leading to pancreatic failure is, first and foremost, a pediatric disease that begins in infancy and reaches peak incidence in childhood.

The question isn't whether we can afford to screen for T1D in primary care—it's whether we can afford not to. Every child who presents in DKA represents a failure of our current system to utilize available knowledge and technology to prevent predictable harm.

The future of T1D care lies not in choosing between pediatric and endocrine approaches, but in integrating them appropriately across the disease timeline. Primary care clinicians should detect and prepare; endocrinologists should treat and manage. Together, this collaborative model can transform T1D from an emergency presentation to a managed chronic condition, saving lives and improving outcomes for thousands of children and families.

Ziegler AG, Bonifacio E; BABYDIAB-BABYDIET Study Group. Age-related islet autoantibody incidence in offspring of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012 Jul;55(7):1937-43. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2472-x. PMID: 22289814.

Haller MJ, Bell KJ, Besser REJ, Casteels K, Couper JJ, Craig ME, Elding Larsson H, Jacobsen L, Lange K, Oron T, Sims EK, Speake C, Tosur M, Ulivi F, Ziegler AG, Wherrett DK, Marcovecchio ML. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2024: Screening, Staging, and Strategies to Preserve Beta-Cell Function in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Horm Res Paediatr. 2024;97(6):529-545. doi: 10.1159/000543035. Epub 2024 Dec 11. PMID: 39662065; PMCID: PMC11854978.

A longitudinal study comprising 32,476 commercially insured Americans aged 0-64 years who developed T1D between 2001 and 2015.T1D=type 1 diabetes.Rogers MAM, et al. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):199.

Excellent paper and much needed. I hope this can pave the way for more wider integration and adoption in the annual pediatric checkups.

Thank you - I hope it does. BreakThrough T1D has submitted an application to the US Preventive Services Task Force, and the American Academy of Pediatrics will consider a resolution in July.